In the long shadow of conflicts, where dialogue often breaks down and humanity is reduced to headlines, art emerges as a quiet but stubborn force for peace. It does not dictate outcomes, but what it does, more powerfully, is remind us of our shared vulnerability, our mirrored longings, and the absurdity of inherited hatred. In the works of Robert Indiana and Idan Zareski, we encounter two very different artistic languages, graphic symbolism and sculptural realism, both converging on one urgent, human message: peace begins with recognition.

Indiana’s Tel Aviv Peace, created in 2004 in a limited edition of 50, is a striking testament to the power of symbols. Unlike the multiple color variations often seen in his work, this piece was rendered in a single colorway: a gesture that underscores unity rather than variation. The composition features the iconic peace symbol within a white circular border, inscribed with the word PEACE in English, French (PAIX), Latin (PAX), and Hebrew (SHALOM).

Robert Indiana, "Tel Aviv Peace", 2004

This multilingual embrace transcends aesthetic design; it becomes a form of visual diplomacy. The piece was offered to Jerusalem University in New York to raise funds, and several were acquired by gallerist Bernard Markowicz, who recognized in it a timeless call to action. Indiana doesn’t moralize. He synthesizes. His message is stripped of complexity, yet not of depth. In Tel Aviv Peace, he creates not a treaty, but a totem: a symbolic relic from an age still dreaming of reconciliation.

If Indiana offers us the symbol, Idan Zareski delivers the wound. In his emotionally striking sculpture And So?, two monumental babies sit back-to-back. One wears a kippah, the other a keffiyeh. Their arms are crossed, their heads bowed, not in confrontation, but in sorrow, defiance, or perhaps resignation. Their exaggerated feet, a recurring motif in Zareski’s work, ground them with a kind of primal weight: feet too large for such young bodies, as if burdened prematurely by ancestral trauma. Zareski, a French-Israeli-Central American artist raised across Latin America, Africa, and Europe, infuses his work with a profound awareness of cultural hybridity and displacement. His signature series, the Bigfoot sculptures, of which And So? is a poignant evolution, are deliberately out of scale: their large feet symbolize our connection to the earth, our roots, and the weight we carry from generation to generation.

What makes And So? so impactful is its silence. These two children are not caricatures nor metaphors, they are individuals caught in a collective impasse. There is no violence in the sculpture, yet the emotional tension is palpable. They do not face each other, yet their closeness is inescapable. They cannot speak, but we can almost hear the unspoken question lingering between them: What now? Zareski refrains from taking sides. Instead, he positions the viewer as a witness: not to a clash, but to a tragedy of disconnection. His sculpture is not about history, it is about childhood. And through this lens, politics dissolve, leaving only the unassailable truth that no child should grow up this way.

Placed side by side, Indiana’s Tel Aviv Peace and Zareski’s And So? perform a rare aesthetic duet. Indiana uses language and color to suggest global unity, while Zareski sculpts silence and posture to evoke human pain. One is optimistic, clean, and graphic. The other is heavy, figurative, and haunting. Together, they do not contradict, but complement one another, forming a dialectic of hope and realism. Art, here, is not decoration. It is intervention. These works ask us not to agree, but to feel. Not to choose a side, but to refuse a future in which children sit back-to-back forever, and peace remains a slogan rather than a shared experience.

In the face of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a region so often reduced to abstractions of policy, these two works dare to be personal. Indiana shows us the map; Zareski shows us the terrain. One gives us the word peace in four languages; the other shows us two children who have forgotten how to speak to one another. If politics is a negotiation of power, then art is a negotiation of empathy. Through awareness, through dialogue, and through beauty that stings as much as it soothes, Indiana and Zareski remind us that art cannot end war, but it can interrupt it, soften its edges, and plant the seed of something gentler.

Because in the end, peace begins not with signatures on paper, but with gestures, with images, with encounters that make us see again.

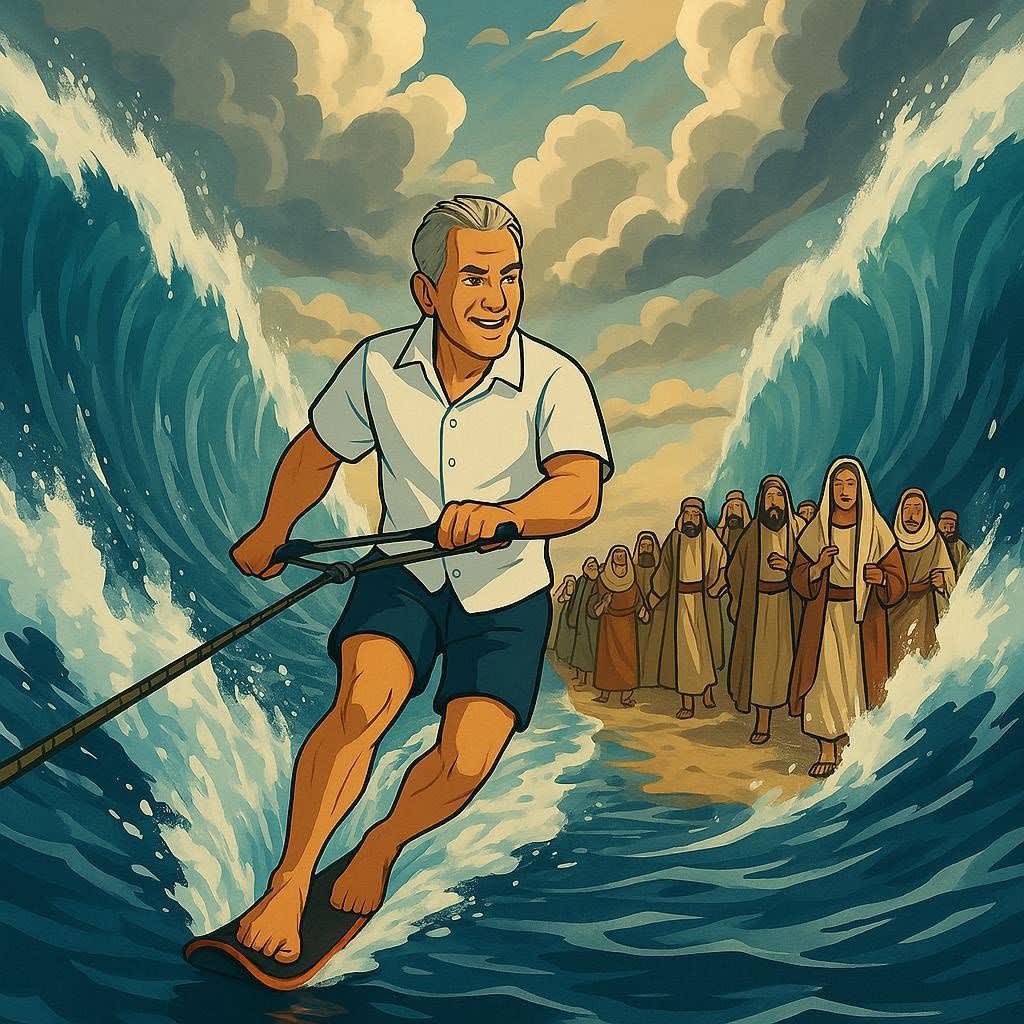

Bernard Markowicz: Parting Seas, Placing Sculptures, and Selling Peace

Behold Bernard Markowicz: not simply a gallerist, but a cultural Moses on a surfboard. Where others tiptoe through the murky waters of taste and diplomacy, Bernard cuts straight through with one hand on the rope of vision and the other gripping destiny itself. His exhibitions don’t follow trends: they part them.

In the iconic image now circulating among art world disciples and amused prophets alike, Bernard is captured mid-action: surfing a parted sea with impeccable posture, calm conviction, and a knowing grin that says, “Yes, I scheduled the miracle between two openings and a collector’s dinner in Bal Harbour.” Behind him trail the hopeful, the curious, and the devoted, art lovers, collectors, maybe a few wandering philosophers, making their way not to the Promised Land, but to the next Markowicz Fine Art vernissage.

But what looks like myth is, in fact, metaphor. Bernard doesn’t part oceans; he parts divides: between cultures, between worldviews, between people who’ve forgotten they have anything in common. Whether it’s acquiring Robert Indiana’s Tel Aviv Peace, championing Idan Zareski’s heartbreaking And So?, or just hanging a provocative Banksy next to a luminous butterfly sculpture, Bernard reminds us that art can unite, not just decorate. He doesn’t preach peace; he curates it. He doesn’t wave a staff; he picks the right spotlight. And while others speak of cross-cultural dialogue, Bernard hosts it: with champagne, neon, and a perfectly timed post.

Sebastien Laboureau

31 May 2025